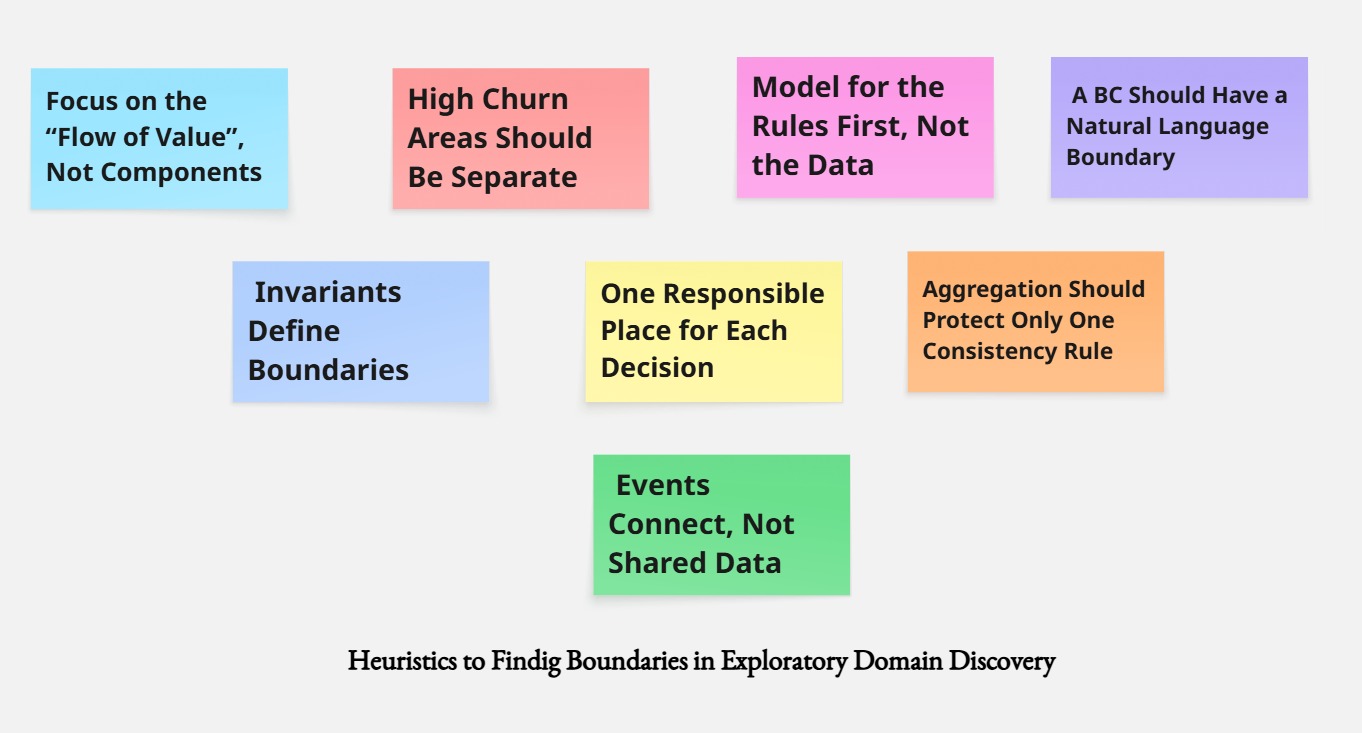

Design Time EDD comes with multiple heuristics.

Below are the heuristics and concrete examples from the YummyFood food-ordering domain example used during Live Demo.

Heuristic 1 – Invariants Define Boundaries

Where a rule must always be true, you have a boundary.

One of the most important heuristics says that invariants define boundaries. Invariants are the rules that absolutely must stay true, otherwise the business breaks. As soon as you identify one of these rules, you usually find the core of an Aggregate or even the core of an entire bounded context.

In the YummyFood example, the Order Intent only has one critical invariant: the customer must explicitly choose what they want from a specific restaurant. That rule belongs entirely to the customer side, not the kitchen, not finance. As soon as payment occurs, a different invariant becomes the anchor: the payment must confirm the intention without being tampered with. This belongs to the financial side, not to restaurant logic. Later, when the restaurant accepts the order, the invariant changes again: the kitchen must produce exactly the meals promised. Each invariant lives in a different world, and those worlds should not be merged. The heuristic makes the separation obvious once you pay attention to what must never break.

YummyFood Example

- An order must not be accepted if the restaurant is closed.

- The price used at checkout must never change after payment.

These are separate invariants, therefore we get separate boundaries:

- Ordering BC – controls status, acceptance, rejection.

- Pricing BC – controls price calculation and price snapshot.

Heuristic 2 – Events Connect, Not Shared Data

Bounded contexts must communicate through events, not by sharing tables or objects.

Another heuristic says that events connect concepts, not shared data. This is a powerful lens during Design-Time EDD. When the kitchen accepts an order, the courier does not need kitchen data. It simply needs the event order is ready for pickup. When payment is confirmed, the restaurant does not need financial details; it only needs to know that payment succeeded. Shared data creates accidental coupling, while events create natural flow. In YummyFood, the prepared order never contains customer financial details, and the payment record never contains the restaurant’s cooking status. Events carry meaning across boundaries without polluting the models with foreign data.

YummyFood Example

Ordering should not read Pricing tables. Instead:

PricingCalculated(orderId, totalAmount)OrderAccepted(orderId)OrderPrepared(orderId)PackageReady(orderId)

Each context handles events it needs, without sharing internal structures.

Shared data creates tight coupling.

Events create loosely coupled, autonomous contexts.

Heuristic 3 – High-Churn Areas Should Be Separate

Parts of the domain that change frequently must live in their own BC.

This heuristic reminds us that high-churn areas should be isolated. Some parts of the domain change constantly: menus evolve, pricing logic shifts, promotions appear and disappear, restaurants modify ingredients. Other parts never change: the concept of a payment confirmation, for example, stays fairly stable. If we place highly dynamic concepts inside aggregates that must stay stable, those aggregates will constantly mutate and become fragile. In our example, menu structures and pricing belong to their own contexts precisely because they churn. If the menu team needs to change combos or dynamic pricing, they should not break the order processing model.

YummyFood Example

- Promotions change weekly

- Menu changes frequently

- Pricing rules change often

Therefore, Menu BC, Promotion BC, and Pricing BC should be separate from Ordering.

Heuristic 4 – Model the Rules First, Not the Data

Start with business rules. Add data later. Otherwise the Aggregate becomes fat and useless.

Another core heuristic is that we model the rules before we model the data. If a team models the shape of the order using only data attributes, they often create an overweight Aggregate that tries to store meals, prices, promotions, customer details, restaurant state, stock status, and kitchen operations. But when we ask what rules does the order itself protect, we discover that it protects surprisingly little: it promises that the customer selected certain meals from a given restaurant at a known point in time. Everything else lives elsewhere. Modeling by rules keeps aggregates small and boundaries clean.

Bad way

Meal has name, price, description, ingredients… This leads to data-driven design.

Correct way

- A meal cannot be ordered if it’s unavailable.

- There can be only one active menu version.

- A combo applies only if all required items exist.

After rules are clear, you add the properties needed to enforce them.

Heuristic 5 – Focus on Flow of Value (not components)

Ask: where is value created, transformed, and delivered?

Another useful heuristic says that we must focus on the flow of value. A system like YummyFood exists to move value from one side to another: a customer expresses intention, a restaurant transforms that intention into prepared food, a courier transports that food, and the customer receives it. Every transformation of value reveals a new boundary. For instance, the order that the customer sees is not the same order the kitchen prepares. The kitchen ticket is not the same object as the package the courier carries. They share meaning but not shape. The flow of value prevents us from merging things that behave differently at different stages.

YummyFood Example: Value Flow

Customer => Order => Pricing => Restaurant => Package => Courier => Delivery

Value moves across contexts. We separate BCs at the points where value changes, not where services happen.

Why it matters

Because Menu Service, Delivery Service, Order Service are meaningless names. Value Flow produces natural boundaries.

Heuristic 5 – Each Aggregate Protects Only One Critical Consistency Rule

An aggregate that enforces multiple invariants is a broken aggregate.

A related heuristic tells us that every aggregate should protect only one consistency rule. When teams try to protect too many rules in one place, the aggregate becomes impossible to maintain. In YummyFood, the financial side enforces payment consistency, the customer side enforces request consistency, the kitchen enforces preparation consistency, and the delivery side enforces pickup and delivery consistency. None of these aggregates attempt to enforce each other’s rules.

YummyFood Examples

Order Aggregate enforces only one critical invariant:

- Order status must follow allowed transitions.

It should NOT enforce: pricing, stock, restaurant schedule, courier availability, and packaging rules. Those belong to separate BCs.

Heuristic 6 – Domain Circular Pattern, Finding Natural Boundaries

Domain Circular pattern appear when a value loops through several actors and returns transformed.

Design-Time EDD also makes use of circular value patterns. Whenever value cycles through a series of transformations before returning to the user, those cycles typically mark natural bounded contexts. For example, the cycle of customer selection, restaurant preparation, courier transport, and customer delivery forms a loop where each stage has its own vocabulary and its own expectations. These cycles make the boundaries feel almost self-evident once you look at them.

YummyFood Example

Order => Restaurant => Kitchen => Package => Courier => Customer => Feedback => Restaurant

This loop reveals natural BCs:

- Ordering

- Restaurant Ops

- Packaging

- Delivery

- Customer Profile / Feedback

Where the cycle stabilizes, you likely have a bounded context.

Heuristic 7- Ubiquitous Language: Why Words Matter

Language reveals boundaries. Underlying all of this is language. Ubiquitous language is not only a communication tool but a boundary detector. In the customer world the word order means commitment. In the kitchen world it means a ticket. In the courier world it means a pickup task. In the finance world it means a payable record. The same word points to different realities. Those differences in meaning are signals. They tell you where a bounded context begins and where it ends. Language separates models even before you build systems.

Example in YummyFood

- Restaurant says Menu Item

- Customer sees Meal

- Kitchen uses Ticket

- Courier receives Package

Same real-world object, different conceptual meaning. Therefore they must be in different BCs, each with its own model and language.

Design-Time EDD ultimately helps teams stop guessing about architecture. Instead of inventing arbitrary services, the model tells you where boundaries must exist, which parts must remain stable, and which parts can evolve. By attending closely to invariants, events, flow of value, language, churn, and consistency rules, the domain itself reveals its proper shape. And once the domain has revealed its shape, designing the actual system becomes far simpler, because the structure is no longer an invention but a reflection of the meaning already present in the business.

[…] EDD Heuristics for Design-Time […]